- Q: How do I sign the petition?

- Q: Can I sign the petition to elect a Charter Commission electronically/online?

- Q: How many signatures are needed?

- Q: What exactly does the petition say?

- Q: I think I signed a petition a while ago. Do I need to sign again?

- Q: What exactly is a “charter”?

- Q: Does Brookline have a charter?

- Q: What is a Charter Commission? Is it like a Study Committee?

- Q: Is there any other way to change our form of government?

- Q: Has Brookline ever had a Charter Commission?

- Q: What is Brookline’s current government structure?

- Q: How does our town form of government compare to city forms of government?

- Q: What is the Town Administrator’s Act?

- Q: What’s wrong with Brookline’s current Town structure?

- Q: How are other communities like Brookline governed?

- Q: If we become a city will we have a Mayor?

- Q: Are city structures less democratic or less representative?

- Q: Are City Councilors more accountable to voters than Town Meeting Members?

- Q: If Brookline moves away from its Select Board/Representative Town Meeting structure, could it ever move back?

- Q: Could the Charter Commission decide to keep the current form of government with Town Meeting and a Select Board?

- Q: Would a smaller legislative council mean more susceptibility to influence from developers or other special interests?

- Q: Would a city form of government cost more than the current one?

- Q: Will Brookline become a city if the ballot question on a Charter Commission passes?

- Q: How do we keep resident voices prominent if we change to a city structure?

- Q: What happened to the student effort for charter change (A Better Brookline) a few years ago?

Q: How do I sign the petition?

The petition must be signed in person, in ink. We cannot accept electronic signatures. But it is easy to find a petition! Just fill out this short form and we will connect you with someone in your neighborhood who has a petition you can sign.

Q: Can I sign the petition to elect a Charter Commission electronically/online?

No, unfortunately. The law requires that citizens sign a petition in person, in ink. Those signed petition sheets are then submitted to the Town Clerk, who must certify each signature as a registered voter in Brookline.

Q: How many signatures are needed?

To have the question whether to form a charter commission placed on the ballot, 15% of a municipality’s registered voters must sign the petition and have their signature certified. In Brookline, that is just a bit more than 6,000 certified signatures.

Q: What exactly does the petition say?

The petition is called a Charter Revision or Adoption Petition. The Signers’ Statement (dictated by state law) reads as follows:

“We request that the (city/town) of Brookline revise its present charter or adopt a new charter. We certify that we are registered voters of that (city, town) whose residence addresses at the times set forth below were as shown below, and that we have not signed this petition more than once.”

How it works: When 15% of registered voters in Brookline have signed and been certified, it triggers the placement of a Charter Commission question on the next available local ballot. For Brookline, that will be the annual May election in 2025.

When it appears, that Charter Commission ballot question (vote Yes or No) will read:

“Shall Brookline elect a charter commission to form a charter for Brookline?”

On the same ballot with that question, voters will be asked to vote for candidates for a Charter Commission. Should the charter commission question be approved, the top nine vote-getters from among the candidates will form the Charter Commission. A Commission then has up to 18 months to do its work of researching and crafting a charter proposal to put before the voters in a subsequent election.

A Charter Commission can consider all forms of government (i.e. both town and city structures) in crafting its charter proposal.

Q: I think I signed a petition a while ago. Do I need to sign again?

If you signed a petition from the student effort A Better Brookline years ago, that signature will still count. We have almost all the sheets from that effort in 2020-2021. However, if you have moved residences within Brookline since you signed a petition, you must sign again at your current address. If you’re not sure you signed, or you want to be sure you’re counted, you can also sign again now. When the Clerk’s office certifies signatures, duplicates will only be counted once.

Want to Sign?: Just fill out this short form and we will connect you with someone in your neighborhood who has a petition you can sign.

Q: What exactly is a “charter”?

A charter is like a local constitution. It’s a document that defines the organization of local government for a particular community, how officials will be elected or appointed, and the duties and powers of each office. A charter provides a guide for all municipal policy and decision-making.

Charters vary greatly from one community to the next (there is no “cookie-cutter version” of a town or a city), which is why a Charter Commission has up to 18 months to research and weigh all the options and then figure out what to propose to the voters of Brookline.

Q: Does Brookline have a charter?

No. In Brookline, we’ve never had a formal charter. In cases like ours, we are guided by the combination of MA general laws, special acts/laws passed by the State Legislature in response to a petition/request from Brookline to change something, and various local by-laws enacted by Town Meeting that address the who and how of our policy-making.

The state recognizes that collection of laws as “having the force of charter,” and the term ‘charter change’ is used to describe the process of altering any aspect of that structure.

Q: What is a Charter Commission? Is it like a Study Committee?

A Charter Commission is more than a study committee. It is a body created by the voters to study local governance and, crucially, to craft a proposal (a charter) outlining how the local government should be structured. Crafting that proposal, which must then be approved or rejected by the voters, is central to the job of a Charter Commission.

Q: Is there any other way to change our form of government?

A Charter Commission is the only voter-driven/grassroots process for proposing changes to our form of government. It is one of two ways Massachusetts law allows municipalities to make changes to their governance structure. Those two are:

- A Home Rule charter process to frame (write) or amend a charter begins and ends with voters. It begins with a petition signed by 15% of registered voters to have a ballot question on whether to form a Charter Commission. On the same ballot, voters elect 9 people to serve on that Charter Commission. If the question is approved, the 9 elected members of the Commission have up to 18 months to conduct a public process of studying the current structure and operations and exploring options. They then write a charter proposal outlining their recommendations for Brookline. That proposal is then submitted back to the voters in a subsequent election for approval or rejection.

- A Special Act charter process, more typically used to amend an existing structure/charter, begins with an appointed charter committee (the committee can be appointed by the Select Board or by the Moderator, for example) charged with looking into the current structure and proposing changes to improve it. There is no set timeline for that work. Any proposed changes go to Town Meeting in the form of a warrant article, called a “home rule petition” because if Town Meeting approves the warrant article, it is sent to the state legislature as a petition from Brookline for a Special Act. The MA House and Senate must both approve (and may make changes to) that Special Act, and the Governor must sign it for it to take effect. For major changes to a charter, a Special Act almost always specifies that nothing will take effect until and unless it is also affirmed by the voters of the municipality at the next local election.

The Town Administrator’s Act is an example of Brookline using the Special Act charter process to make changes. Other special acts over the years established Brookline’s Park and Recreation Commission (1963), the Department of Transportation (1974), and the Department of Finance (1993). More recently, proposals have been brought to Town Meeting to pay a salary to the Select Board and to change the Town Clerk from an elected to an appointed position, but both failed to pass at Town Meeting and so did not move forward.

Q: Has Brookline ever had a Charter Commission?

No. We’ve never had an elected Charter Commission, and we’ve never had a proposal to change the Executive/Legislative structure of government from Select Board/Town Meeting to Single Executive/Council. There have been various committees that advocated for some changes using the Special Act process (see above), but we haven’t considered a major change to our structure since 1915, when Brookline petitioned the legislature to adopt the first Representative Town Meeting in Massachusetts. More than 100 years later, and given that women have since won the right to vote, it seems sensible to consider whether that structure still serves us well.

Q: What is Brookline’s current government structure?

Brookline is a town with a Select Board/Representative Town Meeting structure for policy-making, with a hired professional Town Administrator managing the professional staff and the daily operations/services of the town. (See Q: What is the Town Administrator’s Act?). Our elected government is both part-time and volunteer: Neither Select Board Members nor Town Meeting Members are paid a salary, although our Select Board Members receive a nominal stipend to offset some of the expenses of the office.

Select Board: The executive branch of our government, the Select Board is a 5-member board elected at-large (i.e. by town-wide vote) to staggered 3-year terms of office. The Select Board meets in public, televised session weekly, typically on Tuesday evenings.

Town Meeting: The legislative branch of town government, Brookline Town Meeting today is a group of 255 elected citizens (15 elected members from each of 17 precincts) plus several “at-large” members with voting rights (the 5 Select Board Members, any State legislative representative who resides in Brookline, the Moderator, and the Town Clerk).

Town Meeting typically convenes just twice per year: It meets annually in late May to approve the annual budget for the town and consider any other items (“articles”) in a published warrant, including residential and commercial zoning, other by-law changes, and some non-binding resolutions. Town Meeting typically convenes again in late November for what is referred to as a “Special Town Meeting,” taking up issues unresolved from May or that cannot wait for the following spring. Each convening of Town Meeting lasts between 3-8 nights.

Q: How does our town form of government compare to city forms of government?

The question isn’t simple because there is tremendous variation across the Commonwealth even within town and city forms. Those details, and what might work best and gain the support of voters in any given community, is what a Charter Commission hammers out in its proposal.

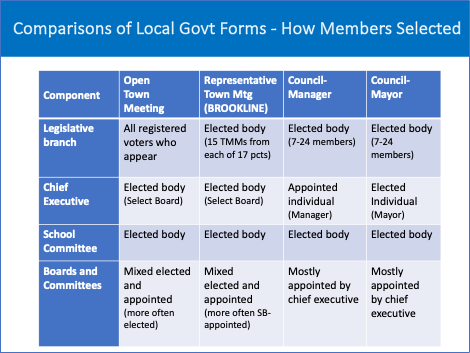

But as a starting point, the Collins Center at the University of Massachusetts provided this simple chart to show the basics:

This chart shows Brookline’s Town Meeting, but Representative Town Meetings in MA range from 90-400, though most are around 240 members. Most City Councils (whether with an elected Mayor or an appointed/hired Manager) are between 9-15 members, although Newton’s is the largest at 24 councilors.

Q: What is the Town Administrator’s Act?

Brookline’s Select Board hires a professional administrator (the Town Administrator) to run the day-to-day operations of the town and to supervise the professional staff. The Town Administrator’s Act was a Special Act passed by the legislature in 1985 that established the role of Brookline Town Administrator, making it formally a part of the Executive Office. Prior to 1985, the job was known as the Executive Secretary to the Select Board.

Brookline has successfully asked the legislature for permission to increase the powers and duties of the Town Administrator three times since 1985 (amending the Town Administrator’s Act and growing the responsibilities of the role), mostly to relieve the Select Board of tasks related to hiring and supervision of staff, and daily operations of the town.

Q: What’s wrong with Brookline’s current Town structure?

On a day-to-day basis, Brookline operates well because we have terrific professional staff who make the town run. But while Brookline has regularly studied and updated our administrative structure to meet growing demands, we have not done the same for our underlying governance structure where policy is made. As a town with a Select Board and Town Meeting, we are still operating with a part-time, volunteer “direct democracy” structure designed for far smaller communities in an era long ago.

The BCCC believes it’s time for a formal process to consider how that underlying structure could be updated to meet the challenges and opportunities of our vastly more complex and fast-paced modern municipal life. That’s the job of a Charter Commission.

Frustrations frequently voiced about our town form of government include:

- Many current and past Select Board Members say that the demands of the job today cannot be met by a volunteer, part-time board. The size and needs of the town have grown too great. People with significant or less flexible job or family care responsibilities can have trouble with the heavy schedule of meetings and other responsibilities of the Select Board, limiting the pool of talent willing or able to serve in the executive role.

- Waiting months for the next Town Meeting to meet and vote on policy decisions adds delay to decisions that sometimes require swifter action, such as responding to new challenges (such as the Covid-19 pandemic) or acting on economic opportunities that arise at the state or federal level. With a single executive and year-round city council, city structures are simply able to respond more expeditiously.

- Residents, advocates, and Town Meeting Members say that a part-time 5-member Select Board (which, by law, is not allowed to work together outside of duly posted public meetings) cannot provide the kind of vision and policy leadership that we need from our chief executive. Any of the city forms of government would give Brookline full-time executive leadership.

- Many Town Meeting Members say that they don’t have the time or bandwidth sufficient to understand the increasingly lengthy and complicated warrant and the $400m annual budget that must be passed each spring. Those with less flexible job schedules or significant care responsibilities also have difficulty attending the longer Town Meetings that have become the norm in recent years.

- With fifteen Town Meeting Members from each precinct whose only job is to vote at Town Meeting, residents complain that they don’t know who represents them in Town Hall, how to get problems solved or issues addressed, or who is responsible for the decisions that get made. That makes it very difficult for voters to hold anyone accountable at the voting booth, a factor contributing to low turnout in local elections.

Q: How are other communities like Brookline governed?

Of the 26 Massachusetts municipalities with residential populations above 50,000:

- Brookline and Plymouth are the only two municipalities with a “town” (Select Board/Town Meeting) as opposed to “city” (Mayor/Council or Council/Manager) form of government.

- 21 of the 26 communities have adopted a Mayor/Council form of government.

- Three have a “weak” Mayor/Council/Manager form of government.

Of the 14 municipalities with populations between 40,000 and 50,000

- Only two (Arlington and Billerica) still have a Select Board/Representative Town Meeting government.

- Ten have Mayor/Council forms.

- Barnstable and Chelsea have adopted Council/Manager forms of ‘city’ government.

Below a population of 38,000, the vast majority of MA municipalities still have a Select Board/Town Meeting form of government.

Q: If we become a city will we have a Mayor?

Not necessarily: the Mayor/Council form of government is just one of the options that a Charter Commission would consider. Becoming a city would mean adopting some form of a council rather than Town Meeting as our legislative body, and having a single executive (either elected, such as a Mayor, or appointed, such as a Manager) instead of a 5-member Select Board.

There are 13 municipalities that have a ‘city’ structure, but still call themselves a town (such as Watertown and Amherst, both of which adopted a Council/Manager city structure).

The specific structure that gets proposed is up to the Charter Commission. Whether that proposed structure is then adopted is up to the voters.

Q: Are city structures less democratic or less representative?

No. Representation is about more than numbers. Democracy demands accountability to the voters, and a well-functioning government must be able to respond in real time to both challenges and opportunities.

The Brookline City Charter Campaign believes that a municipality of our size and complexity could be better served by a legislative body that can make decisions throughout the year, with accountable decision-makers whose votes can be easily tracked and understood by voters. That’s why we want a Charter Commission to consider that kind of change.

Brookline’s 255 Town Meeting Members meet just twice a year to decide a wide range of issues, all of which must have been presented in a public warrant with its own long required vetting schedule. That means we can’t act swiftly if an opportunity arises or if an emergency develops that requires quick, decisive leadership. And at Town Meeting, each decision can involve multiple votes on amendments and motions, making it hard to identify how your Town Meeting Members voted on any particular issue.

A smaller legislative council (typical of city governance structures) is still a democratically elected, representative body. But with fewer members, each is more visible and better known to voters, with their votes and other actions easier to track, allowing voters to hold their councilors accountable. Councils also meet more regularly throughout the year (like the Select Board does now) so policy responses are not captive to the bi-annual Town Meeting schedule. Finally, in the vast majority of communities with a legislative council, it is a paid elected position, reflecting the time such a job takes away from other wage-earning hours.

Civic participation in Brookline is also very high because we have numerous appointed committees and commissions, civic organizations, and a robust non-profit community. That will not change.

Q: Are City Councilors more accountable to voters than Town Meeting Members?

With 15 Town Meeting members (TMMs) per 17 precincts now, it’s hard to keep track of who is voting on your behalf or how they voted on key issues, so it’s hard to hold any TMM accountable for the votes they take. TMMs also have no formal role in governance except voting at bi-annual Town Meetings, so many are not well known by their precinct residents. As a result, many voters don’t understand how Town Meeting works, and voter participation in local elections is very low, often well below 20% turnout. That means each Town Meeting Member is elected by hundreds of their neighbors in a precinct that represents thousands of residents.

Councilors, like our elected town boards (e.g. Select Board, Library Board, School Committee) would have to compete for many more votes, requiring them to explain to voters what they stand for and how their expertise relates to governing. Voters will be able to evaluate candidates during campaigns, track their votes on issues, and replace councilors if they are dissatisfied with them.

With the ability to form legislative committees and council meetings occurring regularly throughout the year, councilors have a more robust legislative structure through which to get up to speed on issues. Because of that, councilors also typically have more regular communications with constituents. Residents, in turn, are more likely to know who represents them and so more easily make their voices heard.

Q: If Brookline moves away from its Select Board/Representative Town Meeting structure, could it ever move back?

Brookline could, in the future, return to a town structure, but history suggests it probably wouldn’t. The possibility is not foreclosed by law, but no town in Massachusetts that has adopted a city structure has subsequently gone back to being a town.

That doesn’t mean that nothing can change, however. Many communities that adopt a charter (whether as a town or a city) regularly review and propose amendments to that charter. In each case, the process of considering change is the same: a charter commission (whether formed by voters with signatures, as we’re trying to do in Brookline, or convened because an existing charter has a review committee and mechanism built in) meets, debates what’s wanted/needed, puts forward a proposal for changes, and then that proposal is voted on.

Electing a Charter Commission, as the current signature petitions are trying to make possible, is the very first step in considering a change in form of government. This campaign believes Brookline should have that formal process of discussion and debate, and then a specific proposal given to voters to consider. Without a specific proposal from a charter commission, all we’re doing is speculating about “maybe” and “what if.”

Q: Could the Charter Commission decide to keep the current form of government with Town Meeting and a Select Board?

Yes. A Charter Commission could propose a charter for Brookline that preserves the town structure. A good charter commission process should include that exploration, but the purpose of convening a Charter Commission (and the animating idea of this campaign) is to give equal weight to the possibility that a smaller, year-round governance structure (i.e. any one of the “city” options available to us) could be more effective, responsive, and accountable than the town structure we have now, and if they find it is, to bring that proposal to the voters. We trust the charter commission process to bring a proposal back to voters that reflects what they’ve heard from the community and thoughtful consideration of all the options, including retaining a town structure.

Q: Would a smaller legislative council mean more susceptibility to influence from developers or other special interests?

Any government structure should seek to promote democracy and diverse representation, and defend against undue influence, so how we can ward against that kind of influence is a great question to pose to a charter commission! Undue influence isn’t just a problem for city structures. There are plenty of people who will tell you that developers have too much influence in Brookline today with our volunteer structure, and that campaigns are too expensive, and so subject to monied interests. Those tensions, along with the need for transparency and voter scrutiny, will continue regardless of the form of government we have. But with a charter commission process, we have the opportunity to think carefully about what guardrails we want to put in place.

Q: Would a city form of government cost more than the current one?

Without the details of a charter proposal from a Charter Commission, especially regarding the size, shape, and method of setting a salary for the Executive and Legislative branches, it’s not possible to project whether a new structure would be more or less costly than our current one. It makes sense that a government structure that pays significant salaries for an executive and/or members of a legislative council will have budget implications. But there is also potential for budget savings when staff are no longer supporting a 5-member Select Board and Town Meeting. The Collins Center presenters at a Brookline League of Women Voters panel in 2023 suggested that in most cases, the budget impact of a change of structure was minimal. But this will be an important question for voters to consider when assessing a Charter Commission’s specific proposal.

Q: Will Brookline become a city if the ballot question on a Charter Commission passes?

No. The current signature petition drive just puts a question on the ballot whether to create a Charter Commission. If it passes, the elected Charter Commission has up to 18 months to research alternatives and write a charter proposal with specific proposed changes. That proposal must come back to the voters for approval.

Even if the Charter Commission is approved, and even if a majority of members elected to it believe some form of city structure would be better, nothing changes until and unless the voters consider and vote on a specific proposal from the commission.

Other municipalities that have been through this process have had very varied experiences. Some elected charter commissions were not able to agree on a proposal (as happened the second time Framingham had a Charter Commission). Many charter proposals have failed to win approval from the voters, as happened recently in Plymouth, and previously in both Framingham and Braintree, even though both those communities eventually voted to change their forms of government.

Q: How do we keep resident voices prominent if we change to a city structure?

This is a great question for a Charter Commission, once it is formed. Brookline has a storied history of civic engagement and grassroots leadership. This campaign comes out of that strong civic tradition and wants it to keep flourishing. We believe a strong proposal from a Charter Commission will update our system of representative government in ways that make it more effective, responsive, and accountable while still providing a wide range of opportunities for participation, voice, and representation in government including volunteer/appointed committees and commissions, voting, public forums, precinct meetings, resident initiatives that flow to a legislative council, and of course elected office. A Charter Commission is the only vehicle that provides a structured conversation among all of us about what we want Brookline to be and then gives voters a proposal for the strongest way to support that vision in our governance structure.

Q: What happened to the student effort for charter change (A Better Brookline) a few years ago?

In 2020-21, a group of students and alumni from Brookline High School formed “A Better Brookline (ABB)” to begin collecting signatures on the same petition we are circulating today. Their strong efforts began a more robust discussion in town about possibly changing our government structure, and they collected about 2,000 signatures before winding down the effort in 2022. ABB graciously gave all those signature papers to the Brookline City Charter Campaign. However, while this campaign picked up where they left off, we need A LOT more signatures to reach the 15% of registered voters needed to put a question to create a Charter Commission on the ballot in Brookline.